Nestled amongst the suburbs of growing cities, or in popular vacation spots, lie timeless gems of golf course design. Here, legendary architects including Alister MacKenzie, Harry Colt and Donald Ross, applied their creativity like master craftsmen and etched their names in the annals of golf architecture history. However, creating this legacy wasn’t an easy endeavour, and just as US President Woodrow Wilson described golf as a game that used “weapons singularly ill-designed for the purpose” golf course construction technologies in this era limited the creative expression of these geniuses.

Over the last 30 years or so, we have been lucky to witness a renaissance in the theory of golden age golf course design and, coupled with modern-day construction methods, new names have emerged to carry the torch of golf architecture and guide it into the future. When playing the modern designs of Tom Doak, Gil Hanse, Mike DeVries or Bill Coore, I often find myself asking a question that feels a little taboo: are all those great classic courses really any better than this?

Modern architects benefit from a growing resource of information and an abundance of living examples of great golf architecture, so it stands to reason that they should be more educated in golf course design than those who came before. Rather than having to rely on limited literature or long journeys by boat or train, modern architects have the books of MacKenzie, Hunter, Simpson, and Doak; and hundreds of revered courses just a short plane trip or drive away.

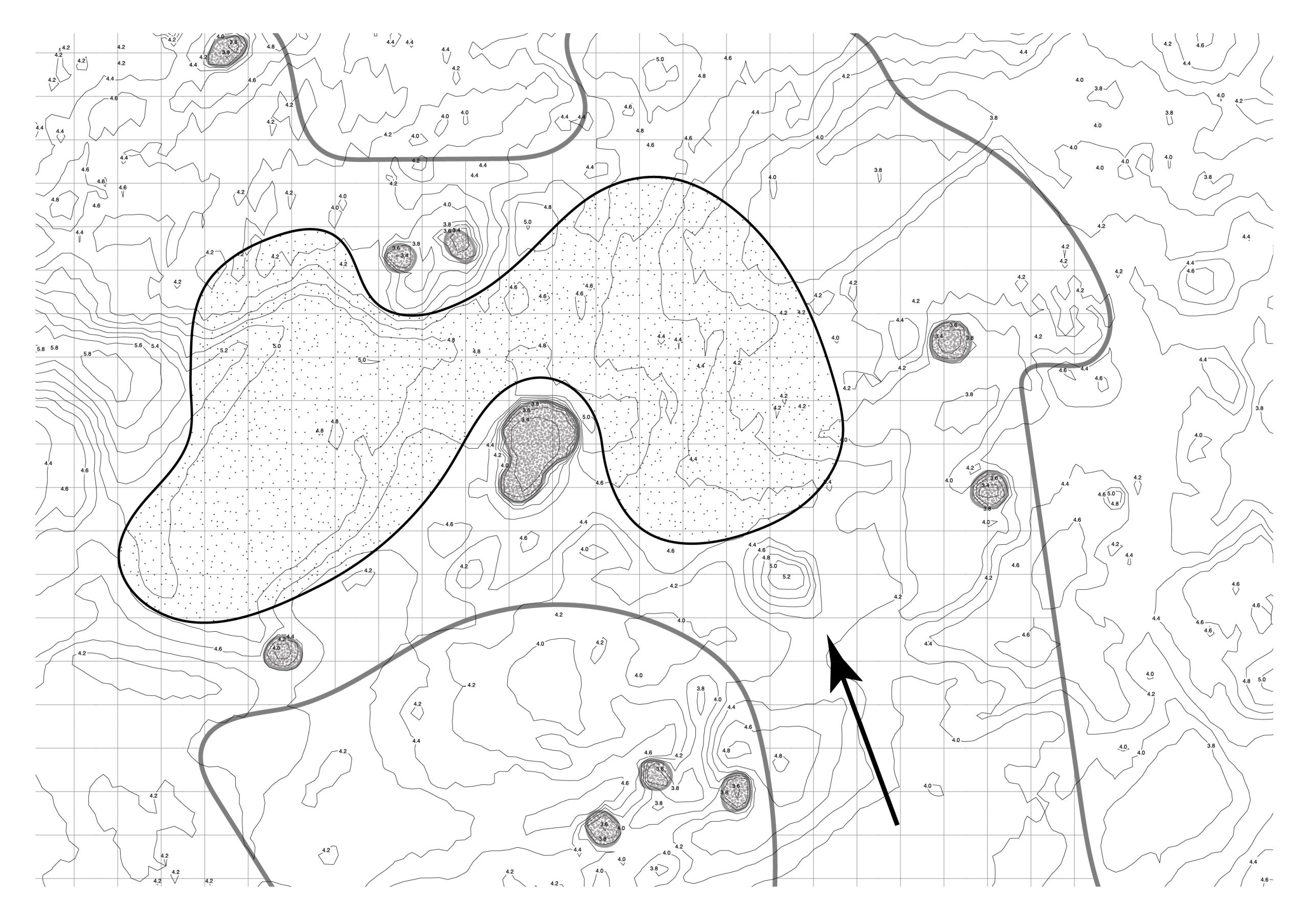

Additionally, we have a plethora of other information available at our fingertips. A quick search of any course reveals Google Earth images and topographical maps, which can be used to study the best courses and understand what makes them great. For instance, a 4K drone flyover and LiDAR scan of the 4th hole on the Old Course is available in mere seconds if we want to visualise the exact scale and shape to the famous bump in front of its green.

An outstanding piece of writing from someone who is going to be a part of this modern golf revolution of which he speaks.

Always impressed by Lukas’ depth of passion and love of his craft, he is in good hands with CDP, a group of guys who simply just get it .

As a lover of the Golden age architects this is a very exciting time , to see the clock being turned back producing courses that are true to the ethics and insights of those golden age geniuses.

What a glorious time to be around watching this abundance of wonderful design coming to fruition , dreams like this of Mr Goggin being realised under the guidance of folks so passionate in their craft ……it’s just so exciting .

Long May this trend continue and I hope to get the opportunity to make the trips to see as many as I possibly can .